PEACHEY Frederick Isaac

-

- 266

- 41 Battalion

- 47th Battalion

- Maroochy Shire

- Yes

- 24 October 1895

- Burnside, Beenleigh, Queensland

- 26 January 1916

- Demosthenes

- 18 May 1916

- Sydney

-

In his words: Having had a somewhat eventful life, and seen the advent of two World Wars, which included active service overseas for three years during World War I and having served in the Army during World War II for its full term, mainly as an Instructor for the 2nd. A.I.F., I have had an interesting life both as a soldier and as a civilian.

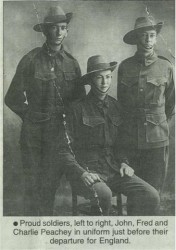

World War I, having taken many of Australia's sons and daughters to the scene of conflict overseas, my two brothers, Charlie and Jack, avowed their intention to enlist in the First A.I.F. at the conclusion of the 1915 harvesting and milling of the arrowroot at Pimpama. As I had not reached my majority, being then twenty years of age for me to enlist required my parents' consent. This my mother was loath to give, saying to me that two should be enough for our family. But when I replied that I would certainly enlist if men were still wanted when I reached twenty-one and that I would very much like to go along with my brothers and other young men of our district offering themselves, my mother consented. My father made no objection to us three lads enlisting, but he said that he could not carry on the working of the arrowroot mill and plantation without us so he and his partner secured release from the five year contract of lease which still had two years to run.

It was on the 26th January 1916 that I enlisted at Victoria Barracks in Brisbane together with my two brothers, Charlie and Jack and in the company of another pal Dave Wilkie who also enlisted. We enlisted in the order of Charlie, Reg. No. 263, Dave 264, Jack 265 and Fred 266. We were placed in camp 'Bells Paddock' in the Enoggera area of Brisbane and issued immediately with dungarees, a hat, boots, blanket and ground sheet plus a kit-bag and later with khaki uniform and great coat. Our accommodation at first was tents, ground floor, and we had to dig out roots of small trees that had been cut off at ground level to make a hollow for our hip as we slept.

After some six weeks, we were moved to Brisbane Exhibition Grounds Camp, and formed into a unit, the 8th of the 31st Battalion. There we were issued with rifles and bayonets and had tuition on the care of them and other equipment such as haversack, water bottle, pack etc. Camp life at the Exhibition Grounds was an improvement to that at Bells Paddock as we had wooden floors to sleep on and the training there was also more advanced and interesting. About the end of April, 1916, a number of us, including the three Peachey boys, were moved from the exhibition camp to the main camp at Enogerra where we then became 41st Battalion men, of the 3rd Division.

On 16th May, in the evening, we boarded a railway train in Brisbane, and traveled all night reaching Sydney some time on the 17th May. We were then transferred by launch to the liner 'Demosthenes" then anchored in Sydney Harbour. She was a majestic steam ship of the Aberdeen Star Line. We sailed away early in the morning of 18th May, 1916. As well as the 41st Battalion and attached units such as Pioneers, A.M.C. etc., the Demosthenes was carrying the 42nd Battalion and attached units and in the hold a large shipment ,of wheat and butter to England. Leaving Sydney Harbour we became one of a convoy of troopships escorted by a cruiser of the Navy carrying, of course, naval guns etc.

We had mainly quite a smooth passage except for when passing through the Great Australian Bight, the sea was very rough. However, during the whole journey I never missed a meal which many of my mates did and I enjoyed everything that was served out to me, even the frozen rabbits, of which the ship carried a large quantity, and stewed rabbits were very often served at our meals. You would hear remarks such as "Oh not rabbits again" and some refused to eat them, but not I.

Our long voyage from Australia took 9 weeks and 2 days and we arrived in Southampton on 22nd July, 1916 in the forenoon. Very soon we were marched off the good ship DEMOSTHENES and to the railway station where a special train was waiting for us. On it we traveled to Salisbury Plain. I was awestruck with the beautiful green countryside and was surprised to see large areas of grazing land nicely set out in well-kept paddocks and fields of wheat, as we neared Salisbury. I had thought that England would not have much open rural land. As compared to Australia it is a small country. But this is not so. It was beautiful weather, too, for our arrival in England. When we reached Salisbury Plain, we were encamped in huts at Lark Hill Camp and only about a mile distant was ‘Stonehenge', a miracle of huge stones placed in a circle with others balanced on top.

One sunny morning towards the end of August 1916, we were marched 6 miles to a huge parade ground where the whole of the 3rd Division of the A.I.F. was drawn up in a ceremonial parade for review by His Majesty King George V. We were issued with new English made military boots at Lark Hill Camp and ordered to wear them for the review. What a mistake that was! By the time we had reached the review area we were sore-footed. Mine weren't too bad but some of the lads had blisters from the new boots, and were not feeling in a happy mood to cheer the King and take part in the Anthem. However, we did present arms on his arrival and stood firmly to attention as he and his entourage inspected us. King George was accompanied by General Sir Douglas Haig. They rode horses and the General dwarfed King George in size and bearing. Seeing them arrive we thought General Haig was our Sovereign King but as they drew closer we recognized them and discovered that our King was only a small man in comparison to the General. Anyway the review was quite a success, only marred lightly by the new boots and I felt proud to have seen our King at such close quarters while taking part in the review. By the time we arrived back at our camp and were dismissed for the remainder of the day, we were glad to get our boots off and bathe our feet. I think the R.A.P. had a busy time attending to blistered feet.

I have no record of the exact date but I believe that it was about the middle of September 1916 that suddenly we had word that the 4th Div. had been in battle at Bullecourt in France, and had suffered heavy casualties there. So reinforcements were urgently required, and as we were now trained men, several hundred of us, including the Peachey brothers, were quickly dispatched to fill the urgent need of the 4th Div.

When we arrived in France, or rather Belgium, we were absorbed by those Battalions of the 4th Div., which had lost hundreds of their men. We joined the 47th Battalion but in different companies. Jack joined A Company, I joined B Company and Charlie joined C Company. By that time, our 4th Division was stationed in a quiet part of the line in the Belgian Sector of the front line, where trenches were well established, and no 'attacks' taking place, and there we held our ground until relieved some weeks later.

My 21st birthday loomed and I felt something was due to happen Well, sure enough it did happen. That evening at about 7 pm. we received orders to be ready in one hour's time and be in full marching order on the Parade Ground. From there we marched to the nearest rail-head, where we boarded cattle trucks. Trains conveyed us overnight to the French River Somme area of the front line. We were guided towards the front line by Army personnel who were acquainted with the area which was the scene of the recently fought Battle of Delville Wood. We passed through fallen bodies of our own men of another Battalion, lying face down just where they had fallen in battle, still grasping bayonet and rifle. I had no way of knowing how many had fallen in that battle only a few days previously. So we took up our positions, to hold recently captured territory of the Somme Area.

For the next 16 days we occupied the front line there which was well established, though the surrounding terrain was pocked with large shell holes, particularly the area defined as 'No-man's Land', which was the area dividing our front line from the German front line. During the three nights of 7th, 8th and 9th November, I had the task and thrill of going out with two of my mates as soon as it became dark, to occupy a 'listening post' in No-man's Land. The 'listening post' was a large shell hole deep enough for no skyline movement, from where we were instructed to give the alarm by firing two shots from one of our rifles in the event of any enemy movement to our front, and then lie low. Our machine gun would then open up from our front line. Of course, there were other 'listening posts, established as well as the one I took part in.

During the night we took it in turns to relax, one at a time. Two of us would be on the alert, and the other could sleep if possible, but in a sitting position on a ledge of the shell hole. So we were off alert for one hour and on alert for two hours in rotation. As it happened, there was no enemy attack during my term of duty there, but if there had been, we were well prepared.

The weather at that time was not at all good, foggy and getting quite cold. During those foggy days my Unit provided a carrying party for the purpose of bringing grenades etc. from a dump at the rear, to our front line trench. So during the day I was one of the carrying party, and for those three nights, in one of the listening posts as well. On the evening of the 10th November my ‘B’ Company was relieved from the front line and transferred to our 'Support Line’, where with the exception of a sentry here and there, we could remove our boots and lie down on our ground sheets and sleep. 'Stand-to' before daybreak on the morning of 11th November 1916 found me unable to get my boots on to my feet, so I took my place in the stand-to in my socks.

Later in the morning our Medical Officer came on his rounds and on examination of my feet declared that I had 'Trench Feet' and ordered me to walk, while I could, back to the 'First Aid Post’, which I did. I had lost all movement of my toes and had to carry my boots slung by the laces to my haversack, and stumped along stiff-footed to the First Aid Post. There I waited for transport, which was via a light railway line and mini-train to the nearest centre. While waiting at the First Aid Post with other wounded and sick personnel, I encountered a fellow suffering from shell-shock. Poor sod! To make things more unpleasant sleet began to fall, and as it reached the earth melted into a slush.

Without a great deal of delay, I found myself on a hospital ship anchored at the nearest French sea port, Le Havre. It was a wonderful change from the trenches and the bully beef etc. that we had to eat, to the comfort of a nice bed and being waited on, with the best food available, by nursing staff instead of our own rough and ready Army cooks. We were ready to leave the French port under cover of darkness that night, but at daybreak next morning I asked the Sister in Charge where we were - only to be told we were still in French waters having been chased by enemy submarines.

We then made the crossing safely to Portsmouth, I believe it was, then by train to Bristol. Why I was sent there I do not know because there was no suitable treatment for me. However, it turned out happily as my cousin, George Peachey, was there in an upstairs ward having been wounded by shrapnel in France. So we had a lot to talk about, and were thrilled to see each other. I was there for a week so George and I had several get-togethers in that time.

My next experience was a train journey from Bristol to Dartford in Kent through the hop-fields, which was a novelty. I was admitted to an Australian staffed and equipped hospital in the town of Dartford and had electric bath treatment for 4 weeks. The treatment consisted of each foot being placed in separate baths, just the right size for the job, filled ankle deep with warm water. An electric current was then connected to each. There my feet remained for 20 minutes each day, followed by massage for an equal amount of time by a nurse. The strength of the electric current was increased from day-to-day and coupled with the massage treatment, brought my feet and toes back to normal.

About 20th December, 1916, I was discharged from hospital and sent to a convalescent camp in Dartford. From there I was granted two weeks leave, so was fortunate in visiting my extended family in Prickwillow, a farming village 6 miles from Ely.

I have no record of the exact date but I believe it was towards the end of January 1917 that I was sent back to France to the 'Bull Ring', as it was called, at Le Havre and there with other mates from the convalescent camp had a week of intensive training before rejoining my unit again, B Company of the 47th Battalion, who at that time were billeted in a country area of France some 50 miles behind the front line. While in that area I was sent to an Army school set up at Avelong. For two weeks I had machine- gun training, in the use and maintenance of the Lewis Light Machine Gun. Our B Company had 4 of these guns - one gun to each platoon.

On rejoining my unit again I was made a Lance Corporal, and Section Leader of the Machine Gun Section of my Platoon, and issued with a Lewis gun and necessary carrier of ammunition filled with magazines, each loaded with 47 rounds of 303 bullets. During the remainder of our stay in that area behind our front line, I gave instruction to my Section as well as to the other sections of my Platoon on the use and maintenance of the Lewis gun. We (the Battalion), in fact, the whole of the 4th Division, were again in the front line of trenches by the end of February 1917, and from then on, continuously it seemed, either in the front line in an attack on the enemy or in the support line right through until about the end of February 1918.

During 1917 we were engaged in several attacks on enemy positions. On 7th June, 1917 during an assault at Messines, my brother, Jack, suffered a bullet wound through his right shoulder and was then off duty for about three weeks. I will not detail all the areas where we occupied the front or support line but they were various and usually in muddy positions where 'duck-boards' had to be placed in the trenches to walk and stand on. Sometimes for a week or two out of front or support we would occupy catacombs dug into the hills captured from the enemy in previous battles. There we were completely underground.

One of those underground areas was beneath a huge French chateau which had been reduced to a pile of rubble by shell fire. Before the battle of Messines took place, a whole hill was blown up by explosives tunneled into it from the rear by our Engineers to the position occupied by the enemy. After the battle instead of a hill there was a huge crater. If I remember rightly the number of that hill was No. 60 and there was another hill, No.63, and at the back of it were catacombs constructed by the Germans earlier in the war. During the earlier part of 1917 British and Australian Forces made use of it. I had the pleasure, if you could call it that, of living in it for a time but mainly at night. We also occupied an area for a time that had sometime previously been held by the Germans, and where they had constructed a few 'Pill Boxes' as we named them.

These 'Pill Boxes' were constructed of thick reinforced concrete and were large enough to shelter a dozen or more men with rifles etc. and at least one machine gun. We were not at all keen on making use of them as the Germans knew where they were, and would try to drop long-range shells onto them. In the well established front lines and even support lines there would be trenches to and from our rear, where we could approach, in secret, and what was termed 'under cover' from the enemy lines. When an assault was made, it was called a 'Hop-over'. All that I can write is that these 'Hop-overs' always ended with many casualties, whether they were successful or not. One such 'Hop-over' took place in October 1917 at Passchendaele Ridge, and it was there that my brother (Jack) John William Peachey made the supreme sacrifice and was killed in action, as were many more of my mates, one of whom was Dave Wilkie.

That was a sad time for me as Jack and I were very close brothers from childhood and all our lives until then. After the 'Stunt' another name for these 'Hop- overs' I sought to find Dave Wilkie, whose unit then was the 41st Battalion, to tell him about Jack. There I found that Dave had also been killed in action. Two of the finest young men that you would ever wish to meet were Jack and Dave, cut down in their prime of life.

That, my dears, is war. May God guard you young men and women who read this from the ravages of war. And so time went on, to me all too slowly, and by the end of 1917 I had the feeling that I had been away from Australia for many years instead of less than two years of actual time.

About the middle of March 1918 I arrived back from leave and found my unit in a state of excitement regarding word having reached us that the German forces had broken through our front line in the vicinity of Albert and Amiens and that we would very soon be on the move to that area. Again I have no record of the exact date, but it was on or about 1st April, 1918 that we formed up in extended order, that is each man spaced three or four paces apart and in full battle dress. In broad daylight, we were given the order to advance from our positions on our side of the Albert to Amiens road. The road was lined on either side with trees and under their cover from overhead view we formed up and established a Headquarters.

We expected that we were to meet German Forces right out in the open, but that never happened. The first thing that we met was a barrage of short-range shell fire. We called them 'Whizz-bangs' as if they went beyond us there would be a whizzing sound and then a bang as the shell hit the earth. They were loaded with shrapnel and caused a number of casualties among us.

During the early part of the night, our patrols advanced to find out where the Germans really were and our Sappers went forward as far as possible and prepared emergency positions for us. These were a series of large shell holes hurriedly joined together to form rough trenches and before daylight the next morning we took up positions there. Our patrols had located German positions in a sunken road where they were heavily armed. The German positions were less than 300 yards from our hurriedly made positions. So for the next few days we remained there holding our position, under orders to "Hold on at all cost."

The unhappiest day of my life was April 5th,1918. At daybreak, the German heavy artillery put down a terrific barrage of shell fire on Durnacourt and annihilated the French Forces causing a gap in the front line on the immediate right flank of A Company of my Battalion. 'A' Company men held off the enemy at our immediate front until they ran out of ammunition. At this critical point I was ordered to take my gun and what was left of my section, to assist 'A’ Company. Having used most of my ammunition to hold off the Germans at the front of 'B' Company, I had less than 200 rounds for my Lewis gun and one man as well as myself, Ernie Jarman, who carried the ammunition in a carrier, except for the magazine of 47 rounds which I had mounted on the gun, plus his rifle and personal supply of about 25 rounds.

In short, I opened fire on the enemy, when-ever they appeared within range, but they persisted in rushing through the gap, despite my fire. Many of them fell as they did so. When my gun was out of ammunition my No. 2, Ernie Jarman, loaded my magazine with his own personal ammunition as my gun was more effective than his rifle.

When no further ammunition was available and I realised that we would very soon be surrounded by the German forces, I appealed to the Sergeant in charge of 'A' Company (their Officer had been killed) to give us the order to fall back to our support line, where I would surely find ammunition for my gun. He refused saying, "Our orders are to hold on at all cost." In no time at all, the opportunity to withdraw was lost as we were surrounded by the enemy. So I had no option but to do what I had been taught to do if such a situation transpired, namely to destroy the usefulness of my Lewis gun by- removing the bolt and the pinion and stamp them deep into the mud of which there was plenty. This I did and I am not ashamed to say that I had tears in my eyes while doing so.

The Germans at that stage opened up a barrage of grenades. They were a type of German grenade that we named ‘plum puddings' as they were shaped like a plum pudding with a shaft attached for insertion into the barrel of the gun used for propelling them. Fortunately they fell short of our position though they were very close and shook the earth near us.

Then the Germans rushed our position and we had no option but to surrender to them. They quickly marched us back, at the same time stripping us of all arms and equipment. What a feeling of frustration it was to me, being ordered by the enemy to leave our position and march into enemy-held territory! Soon after we had passed their lines we were subjected to shell fire from our own artillery. As the shells exploded in our vicinity, the German soldiers would race to any cover available and at the same time keep us covered with their loaded rifles, whereas we stayed where we were, out in the open. Even though we were their prisoners, we showed them that they could not make us run for cover, as they did.

There were 41 of us there and 5 others who had been walking wounded. These five had been taken to hospital. During that second day blankets, one each, were provided for us, but when separating them from the heap in which they, had been dumped, we found that they were infested with maggots. So we refused to accept them through our interpreter, a man called Zimmerlie who was able to speak German.

There was great consternation among our German guards for a while. Then word was passed on to us that they would remove a few of the blankets, the worst infected ones, and that we must accept the others. Failing to do so would result in our Sergeant being placed in solitary confinement in an underground cellar for three days without food and only a little water to drink. So we accepted the blankets and spread them out in the sun to freshen them before using them.

Our water supply for the Prison Camp came from a deep well situated near a wood about a mile from the camp. Each evening a German sentry would conduct about a dozen or more of us to the well each carrying 2 x 2 gallon tins of suitable design, and we would raise the water from the well by means of a rope and windlass and fill the tins. I had noticed that the sentry had counted only the number of tins but not the men. So I arranged with one of my mates, W. Smith, to take only one tin and 1 would do the same but for us to carry them on the side nearest to the sentry. Then when the tins were all filled, Smithy, as we called him, would carry the two tins back to camp, and while the sentry was hurrying the men who were working the windlass and filling the last tins, I would disappear into the wood. This I did. I have no record of the exact date on which my bid for freedom took place, but from memory I believe it was on or about 10th May, 1918.

A few days before escaping I had swapped my good 'Putties' away to a German sentry for half a loaf of their rye bread. This I had for food, carrying it in a billy-can, that we were allowed to have, to warm things up in. It was a 7 lb syrup billy type with a wire handle and blackened on the outside from use on an open fire. I found mustard seed growing in a field, which was just mature and tasted good, so I ate some of it, and only ate small quantities of rye bread each day.

I was free for three nights during which I moved stealthily through the countryside avoiding artillery gun emplacements and all other enemy fixtures of any kind. During daylight hours I would hide myself in the woods or whatever cover was available. Late in the third night I passed through what I believe was the German support line. It was in a sunken road or cutting and the German soldiers lying down asleep, about 3 feet apart, some of them snoring. I lost no time in passing through between them and scaling up the bank as quietly as possible.

Daybreak was fast approaching when suddenly 1 saw a line of enemy soldiers in extended order, coming towards me. I had to turn and hurry back a little way and move around a hill to my right and then up the hill as 1 knew that they would avoid the hill because of the resulting skyline movement.

On top of this hill I found several large shell holes and chose one deep enough for concealment from the surroundings. When it became daylight I could observe the German front line position and so made a plan in my mind of how 1 would make the attempt to pass through it, as soon as nightfall allowed me to move forward again. I, then having found an old German greatcoat in the shell hole, used it to cover myself and had a snooze for about an hour.

Luck was not with me it seems, because just then the burly figure of a German soldier appeared and stood on the edge of my shell hole hide-out, armed with a revolver in his holster. Surprise to him and shock to me took place.

He lost no time in marching me to where more German soldiers were seated, apparently making use of the fog to air themselves from the underground shelter that I had observed the doorway of earlier that morning. There sat a Sergeant-Major and into his notebook, he entered full particulars of my capture, given him by my 'captor'. The Sergeant-Major posted a sentry on either side of me and with himself in the rear marched me to the self-same underground shelter. When we reached the inside of it there was a Prussian officer of high rank, probably a colonel, sitting at a small table with a map spread out before him.

After a conversation (if you could call it that), he shouted, "Well you British soldier you will be put up against a wall and damned well shot and good enough for you." and thumped the table with one fist, while pointing to the door with his other hand and saying 'Gehtl (a German word that I understand to mean 'go'). So the Sergeant Major gave the order to the sentries and I to 'about turn' and 'quick march’. They marched me back some fifteen miles or more to where there was a barbed wire prison camp and locked me up in a small galvanized iron room, barely six feet wide each way. There was a strip of 30 inch wide wire-netting fixed from wall-to-wall on one side of this room which was the only furniture. I sat on that for a time and that night used it as a bed. They placed a small container of water on the floor for me to drink, but no food. I understood that I would be shot the next morning.

Just before dusk, a party of prisoners in English uniforms arrived and the sentry opened the door of my temporary room, and they threw in tools that they had been working with - picks and shovels - under my wire netting bed which was suspended about three feet from the concrete floor. That was the end of another of the longest and most disappointing days of my life.

Before it was quite daylight the next morning the same old sentry that I had seen the evening before unlocked my door and took me to the near-by cook-house. There, he asked an orderly to give me some Kaffie holding out his own Dixie lid, so they gave me some of their imitation coffee to drink. The sentry asked them to give me some rye bread, saying "da brot, brot." One of them broke off a chunk of bread and the sentry urged him "da marmalade" so they whacked some marmalade onto it and that was my breakfast. The sentry then hurried me back to my lock-up before the corporal made his appearance.

But it was a fierce Sergeant Major who next unlocked the door a little later and ordered me out onto a nearby parade ground, where there were about a hundred more prisoners lined up in fours ready to march. They were English and all appeared to be quite young lads. I was placed at the rear of them with a sentry on each side of me. The Sergeant Major then ordered me not to speak or move.

When all was in readiness, we were marched off and continued marching for some hours until we reached Perone, a town that I knew as it had previously been held by the British and French forces. What happened next was that we were marched into the town square, which was a large one like a grassed park. All the other prisoners were allowed to sit down on the grass when we arrived there. After much discussion between the officers, pointed to where the other prisoners were seated.and so I was allowed to join them. My being shot was never mentioned again, and I was treated as all the other prisoners.

However, we were moved a long way back into German held territory, and traveled mainly by train to a Prisoner of War Camp situated deep in the then German occupied Alsace Lorraine. The building we were housed in was a previous prison factory with high walls, and small windows very high up in the walls. Our bedding was straw palliasses on the concrete flooring about 18 inches apart. There was a row on each side of the building with a space of about 5 feet down the centre.

There were, I believe, at least 200 prisoners in the one building. The toilet arrangements were deplorable. At each end of the building a small cubicle of about 8 ft in width by 16 ft held large open wooden tubs, two in each cubicle, about 30 inches high by about the same in diameter at the top. These were the only facilities provided and the doorway to each cubicle was not even provided with a door. The outer doors were kept locked all night and it is not hard to imagine what the atmosphere would be like in the building during the night. Servicing of these so-called toilets had to be done by some of the prisoners and what an awful task it was!

During the day we were made to work. Some of the time was spent at a goods store loading or unloading food supplies for the German Army. Other times we were working out on the roads or loading gravel for repairs to roads.

After a few weeks living under these unhygienic conditions, I became ill and delirious so they took me off to hospital. Though I knew nothing at the time, I later found myself to be in a sanitarium up in the hills of Alsace-Lorraine. Things there, of course, were very different. The first thing that I became aware of, as I came out of my delirium, was that I was in a hospital bed with a nurse standing beside me. The American patient in the next bed, John Norton, told me that the day they had admitted me, I was lying there with my face covered with a sheet. When the doctor lifted the sheet and had a look at my face, he said just one word, "Kaputt" meaning that I was done for.

After doing his rounds of the other patients he came back and had another look at me and found that I was still alive. He then became excited and told the Nurse and Wards-man what to do. They put hot wet packs around my chest and back. Apparently,it was three days since I had gone into a delirious state at the prison. The wards-man told me that I was suffering from double pneumonia, both lungs being affected. No doubt that it was caused by the conditions imposed on us at the prison building.

But I was only up and walking about for a brief two days when I was taken back to the prison camp. It was not the same huge unsanitary building where they had put me, but smaller place with better ventilation. However, the very next morning I was sent out to work with the other prisoners. The job was to shovel gravel from a large heap on to a truck. After the first few shovels of gravel had been hoisted, I collapsed and fainted.

I remember being in the prison camp afterwards where they had taken me, and wondering if I were going to die. The same German doctor from the hospital came to my side and examined me. By the look on his face I assumed he was surprised to see me back there and very much alive. He made me understand that most of the prisoners there would shortly be sent to Russia and asked if I would like to go.

I said "Please leave me here." He then indicated that I would not be sent to Russia.

I remember thinking of my home and family in Australia and praying to God that I would get well again. Fortunately my prayers were answered and 1 soon became well again.

However, time had dragged on into early August 1918 and many of my fellow prisoners were, sure enough, packed off to Russia with about 30 of us remaining for a few days. We were then moved from there to a quiet place where there were a few huts for we prisoners to occupy surrounded by barbed wire. The guards were also housed in the same enclosure but in separate rooms. We were put to work and my job was to assist a German Army man working as a carpenter. His name was Johan Nowak.

I confided in Johan that I had made a bid for freedom and would try again, but not while I was in his charge. He urged me, in broken English, to give up the idea, as the border between Alsace Lorraine and France proper was impregnable, and there was no hope of me getting through it. He said also that it was several hundred kilometres to the fighting lines and that the war would be over within the next two to three months.

As time went on the demeanor of our guards changed from surliness to a more quiet way of speaking to us and they appeared to close their eyes when some of the civilian women and children approached the barbed wire fence and spoke to us. From under a skirt or apron often appeared some bread or other items of food and were passed through to us. Our ration of food supplied by the German Army was meagre, and we appreciated the gifts through the barbed wire very much indeed. No doubt, the blockade, spoken of by the Prussian Colonel, was having its effect on the German Army as well as on the civilian population. Though generally speaking the guards looked well enough fed, and for that matter the civilians did too.

On the evening of 11th November, 1918, the officer in charge of our sentries, called our Sergeant to go with them for a short time. When he returned to our quarters, he was carrying some Red Gross packages for us containing several loaves of dried white bread, some tinned coffee and milk - Nestles I believe it was - anyway it was delicious added to hot water as a drink. There was some chocolate too, I think.

It was the first time that any Red Gross parcels had reached us. The Sergeant told us that he had not been told by the German Officers what had happened, but that we would know by the next day. We had never dared to sing any of our marching songs before since becoming Prisoners of War but we did that night. Next morning, 12th November, we were told through our Sergeant that we were being moved from there and would cross the River Rhine into Germany itself.

We were marched away from the prison camp and to the nearest village towards the River Rhine. When we reached the village square we were met and halted by a group of armed French civilians, about 20 of them. We discovered later that they were a Vigilance Committee set up to disarm the German guards and to take charge of us.

So within a short time they had disarmed the Germans, stripped them of their equipment and allowing them to take only items of food, sent them on their way to cross the Rhine without us. We were kept under control by the Frenchmen and marched into a building, probably the local Community Hall. It was only then that we were informed by the French leader that an Armistice had been signed by both sides and that we were now free.

John Norton, my fellow American from the hospital, and I kept together from then on. We were told it might be a couple of weeks before any transport could be arranged. So John and I talked over the situation with several other American soldiers who were there too and we decided to scale the wall and make our own way back to our own Forces. With the help of the other Americans John and I scaled the wall early that night and trudged 13 miles, I believe it was, to the nearest rail-head. We were fortunate that before morning a train pulled in and we boarded it. It was heading to the border of Alsace-Lorraine, or rather to a village not far from the border with France proper.

We lost no time in walking through the village towards the border. the village was on the lower slopes of the mountain of hills, along the top of which was a huge barricade of barbed wire with an opening that had recently been cut through it. So that was the point where John Norton and I passed through and found ourselves to be not far from the French town of Nancy. The date was now 15th November, 1918.

On the outskirts of Nancy we met a regiment of black Americans, who were billeted there. They gave us food and also gave us a change of boots. The makeshift German boots that we were wearing were ready for the scrap heap.

By that time John and I were so tired from all the walking that we had done, as well as the considerable train travelling, that we slept and slept at Nancy, until means of travel were found for us, to convey us to Allied Headquarters located towards the French coast. The name of the nearest town has slipped my memory, but I do remember the wonderful feeling that I had knowing I was free again and, God willing, would see my loved ones again.

I parted from John Norton at the Allied Headquarters and within a few days crossed the English Channel by ship, from Calais to Dover. I well remember seeing the white cliffs of Dover (so white they are) as we approached England. From Dover I traveled to London by train and reported to the Australian Army Headquarters in Horseferry Road.

There I was fitted out with a new khaki uniform and greatcoat, as well as new underclothes etc. A considerable amount of back pay was due to me and so I collected that, went to a barber for a much needed hair trim, had a new issue razor and enjoyed the facilities Buckingham Palace Hostel for a couple of days. Whilst there I met up with W. Smith (Smithy) again who had assisted me to escape from the Etricourt Prison Camp as previously recounted. We were able to swap experiences that had occurred to both of us since that day. My No.2, Ernie Jarman was there, too, and he and I had a joyful time together.

We were granted five weeks leave on full pay to visit relatives or friends in the British Isles and given a leave pass to cover that period of time. Therefore I again visited my aunt, uncle and cousins at Prickwillow and while there, my cousins, who had pushbikes, rode with me as I walked the six miles to Ely. There I hired a bike for a week. I had never ridden a bike before, so that evening I had some practice riding it up and down the lanes at Prickwillow. That visit of mine to Prickwillow lasted about two weeks and I enjoyed it very much. I went on from there to Scotland and visited my Uncle Alex and his family again in Dyce in Aberdeenshire. My cousins there gave me a great time showing me round their beautiful country rills and dells.

Ernie Jarman and I returned from Scotland at the end of our five weeks leave back to the Horseferry Road Headquarters. From there we were dispatched to Weymouth Military Camp to wait for a troop ship to bring us back to Australia.

At long last the good ship Nevasa was ready for us and we boarded her on the afternoon of 5th March, 1919 in Portland Bay. Her dimensions are as follows: Tonnage (gross) 9070 tons, Length 490 ft, Beam 56 ft, Speed 14 knots. We steamed slowly out of Portland Bay at 6 am on the 6th March, 1919 and how nice it was to be on our way back to Australia. There were a total of 1375 Army personnel on board including 10 nurses 51 officers and 1314 other ranks, all members of the 1st. A.I.F., plus the Captain and crew.

The ship took on coal in Colombo and that operation being completed we left Colombo at midday on 1st April. Since leaving England the weather had been very good but shortly after leaving Colombo we ran into rather heavy weather, which continued for the greater part of the journey across the Indian Ocean. However it never interfered with my enjoyment of the journey.

When we were two days out from Fremantle we received orders by wireless to change course and proceed direct to Albany, which we did. We gained our first glimpse of Australia on the evening of 12th April. It was midday when we dropped anchor at King George's Sound, off Albany. The West Australians were taken ashore on smaller craft and we continued on our way.

We had a pleasant run across the Bight and reached Adelaide on the 18th in the morning. The South Australians were taken ashore and the Tasmanians transferred to another ship, the "KASHMIR" thus saving us the extra journey to Hobart. We left Adelaide waters the following day and another quiet run brought us to Port Phillip Heads, which we entered at daybreak on 21st April. There, of course, the Victorians were cheered by us as they left our good ship Nevasa and at 11 am on the same day our journey was resumed.

The Heads of Sydney Harbour came into our sight on the morning of the 23rd. We anchored in Sydney Harbour and cheered off our N.S.W. men and sisters and officers too, leaving only the Queenslanders and the ship's captain and crew to continue the journey to Moreton Bay, leaving Sydney Harbour later the same day.

We arrived and cast anchor in Moreton Bay on the 25th April and although I have relied on my souvenir booklet for the dates and times of our journey since leaving England, the fact that we arrived in Queensland waters on Anzac Day 1919 is fixed firmly in my memory. Owing to an influenza epidemic being prevalent, we were landed at Fort Lytton, the quarantine station at the mouth of the Brisbane River on the morning of 25th April.

There our clothes, kit-bags etc. were fumigated and we were put through a rigid medical examination and told we would be there for almost a week. 1st May was to be the day of our movement into Brisbane, so letters were dispatched to our parents to inform them when and where to meet us.

May 1st 1919 was another red-letter day for on that day we boarded one of the Brisbane River pleasure boats at Fort Lytton. There were two of them, the "BEAVER" and the “KOOPA". It was the Beaver that took my brother Charlie and I and the other Queensland contingent to land at Kangaroo Point. There we were met by our parents and after some delay at the Finalization Depot, in the company of our father and mother, we went on to the Railway Station at South Brisbane and traveled by train to Ormeau arriving there in the evening just after sundown.

As the train pulled into the station, the first sound that greeted our ears was the many friends and relatives awaiting us, singing 'Home Sweet Home’.

-

- Amiens

- Bullecourt

- Messines

- Passchendaele

- Somme

- Returned to Australia

- 25 April 1919

-

Nambour (Maroochy Shire) Roll of Honor Scroll, Private Collection, Nambour (this scroll was available for sale to the public after the war)

- Colleen